Forums › Library › Knowledge Base › How The Butterfly Stroke Works

Please type your comments directly in the reply box - DO NOT copy/paste text from somewhere else into the reply boxes - this will also copy the code behind your copied text and publish that with your reply, making it impossible to read. Our apology for the inconvenience, but we don't see a convenient way of fixing this yet.

Tagged: butterfly, introduction

-

AuthorPosts

-

August 23, 2018 at 11:40 #19540

Admin Mediterra

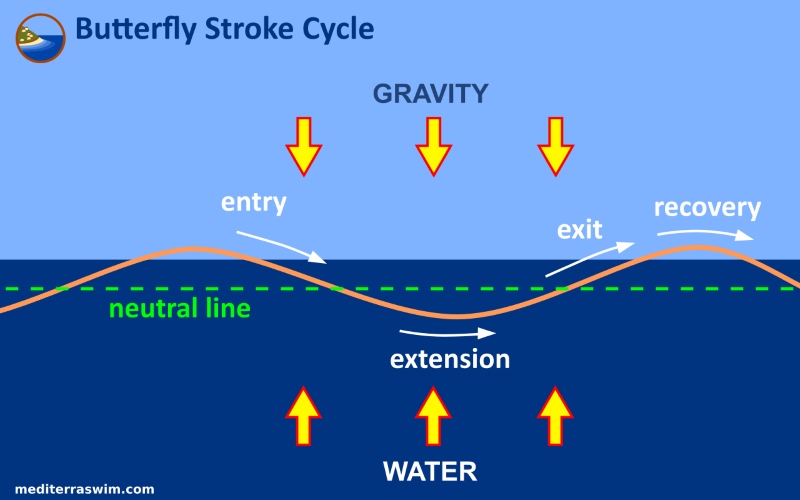

KeymasterButterfly is a stroke that requires ‘dynamic balance’ where you are playing off of gravity and water pressure, sliding above and below the neutral line on a controlled wave path.

You may divide the stroke into four sections to work on your skills for working with gravity and water:

- Entry

- Extension

- Exit (including the underwater pull)

- Recovery (sweep of the arms)

The objective is to create a stroke pathway that has minimal amplitude (height and depth above and below that neutral line) so that most of your action is about driving the body forward more than upward against gravity. This is the pathway of least resistance.

The more the whole body can follow the same path along this curve, legs sliding behind the head and shoulders, the less resistance you will face in moving forward.

Reducing Height

The reason for the body to break the surface is to allow a breath and to allow the shoulders to clear the water long enough to let the arms sweep forward. But any body part projecting above the surface of the water more than necessary is extra effort exerted against gravity, taking away from your forward movement.

The higher any part of the body goes above the surface, the harder gravity will try to push your body on the way down, trying to drive it deeper. This all increases the amplitude, making your pathway forward, longer and slower. So minimizing surface time, height above surface, and minimizing depth are two of your main technical tasks in the stroke.

The Exit

The Exit is where you take the underwater stroke, creating thrust, and you aim the body with that thrust. The more forward you drive the upper body, the lower your amplitude.

The thrust has to be powerful enough to slide the head and shoulders above the surface for enough to allow for the breath and recovery sweep. The closer to the surface that you initiate the stroke, the easier it is to thrust the upper body out of the water – but not too close!

This is often where the stroke cycle gets messed up. If you do not get this step of the stroke set up well, it will mess up the rest of the stroke for that cycle. Your next chance to get things back no track is in the extension.

Recovery

This is where you sweep the arms forward, back into streamline as the upper body plunges back into the water.

A critical shoulder-safety piece here is to have a strong enough thrust out of the water so that the shoulders can clear the surface.This also requires that the underwater stroke be finished at just the moment the shoulders break the surface so that they can immediately use that precious, short time to sweep forward before the body plunges back in.

During the sweep, because of the way the shoulder joint is designed, the elbows and lower arms should ideally be below the shoulders, closer to the surface, or at least level, in order to lower the risk of shoulder tendon strain and injury. When the elbows are flung behind the back and arms swept forward behind the scapular plane, this increases the risk of shoulder injury. And the higher the arms go above the surface, the more you are working against gravity unnecessarily, the harder gravity will shove the body deeper on the entry.

So, keep the arm sweep close to the surface.

Entry

The entry is where you have the opportunity to determine how deep the body dives, in response to gravity’s press.

By leveling the arms at the right moment, while letting the head and upper spine slide downward, absorbing the last of gravity’s push, you can control the depth of your curve, staying closer (but not too close) to the surface, where you then choose a longer underwater stroke or a quicker return to the surface to start the next one.

Better Kick

During the recovery and entry, the legs do not rise above the surface like the head and shoulders do, so there is some unavoidable drag as the legs plow through the water where the head and shoulders just slide over the top.

There is a first kick that occurs with the underwater stroke, at exit, and (often) a second kick that occurs at the entry.

This unavoidable drag can be reduced by developing a kick that comes from the core, from the center of the body and minimizes how much knee bend is used in the kick.

A core-driven kick will allow the legs to stay more streamline behind the torso, while a thigh-driven kick requires the knees to poke below and the heels to rise above the profile of the torso.

The more the swimmer relies on a knee-bend kick, the more drag (putting on the brakes!) created, reducing momentum. It takes understanding and discipline to build a strong abdominal kick, but it is worth the effort to get it because you reduce the work the upper body must do i compensation for that extra drag.

Extension

The next technical task is to let water do some of the work for you. After the body enters the water, diving downward, water pressure will eventually push the body back up, and you can determine when and where it does. You do this by how quickly your level the arms and extend the body line horizontal, and by how aggressively you extend that body line, curving upward toward the surface.

With body line fully extended, stretched and slender, you may wait for the water to bring the body closer to the surface so that you may initiate the pull at closer to the surface where you will not have to pull through as much water to break the surface.

You control the depth of your dive by how quickly you level the arms and begin extending. There is a sweet spot, waiting for the shoulders to drive just below the neutral line then level out. If you extend too early, the loses momentum at the surface. If you extend too late, the body dives too deep and then you either must wait longer for water to lift the body or pull your self toward the surface from a much deeper position, thus working against the water.

You control the length of your underwater glide by how quickly or slowly your extend your body (curving upward toward the surface). The faster your tempo the sooner you need to have water press your body up toward the surface.

You control the amount of momentum preserved by how super-stretched you keep your body line and how closely your legs slide behind your torso on the same path.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to view attached files. -

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.