by Admin Mediterra | Sep 27, 2020 | Open Water, Practice Design

If you feel some tension between your need to maintain swimming fitness and your need to carefully integrate new skills that can’t quite hold up under regular training stress yet, you may wonder how to get the best of both, without losing too much from either.

Early on in a season of acquiring new skills or in reformatting some big feature of your stroke, you may need to slow things down to get that new movement pattern etched into your nervous system. This may mean doing more drill and short stroke segments and short repeats for a while, until those skills feel more familiar, more easily performed and sustained under easy swimming conditions. Eventually, you may feel ready to start swimming longer, uninterrupted distances and your attention and control over technique will feel ready for it.

However, you may already have a good foundation of skill built up and are just making some minor adjustments that are not so hard for you to stay focused upon under normal fitness training. Or, you may be starting a process of making big changes, yet you still feel the pressure to maintain more intense training while you try to integrate those new skills into it.

Granted, it will be better (easier and shorter) in the long run if you can ‘slow down’ for some period of time to more carefully integrate your new skills under easier conditions that allow you to hold attention and form successfully. But you can still do whole stroke swimming with some or most of your new skills, if you choose just one or two cues at a time and you hold yourself to a high standard with those.

Use your drill and short-slow-and-careful stroke work in the first part of your practice and during active rest between fitness sets. Use this time to set a few, very specific cue that you want to insert into your fitness work and maintain. This kind of intention and concentration will actually make your fitness work even more challenging!

Using the activities you’ve learned in your live lessons or in the videos, just take some time to tune up your sensitivity and control over a few particular parts of the stroke a drill, then move into whole stroke swimming holding just one or two cues at a time. Within whatever normal swim set you are doing, choose a distance or duration in which you will hold your attention on that chosen cue – this too will be like lifting weights, and you will notice attention fatigue.

So, choose 2 or 3 cues and rotate though them at regular intervals, while continuing to swim whole stroke. This is called ‘swimming with cues’. If at any time while swimming along you lose the feel, lose sensitivity, lose control, then you can stop for a moment to move into drill mode to regain that control, and then resume the set.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 27, 2020 | Open Water

Pools are, by their design, controlled environments. The temperature and chemistry is tightly regulated. The length is fixed. The lanes are marked out. The number of people might also be limited. We get used to the consistency and predictability of this environment. We might even become surprisingly finicky when those minor conditions change even a slight amount – regular pool swimmers notice!

However, open water in a natural setting is wild water. It is not subject to our controls. When practicing in open water, there can be a great deal of variation in the conditions from day to day, in addition to any changes in your own person. When those conditions change, your expectation need to change also.

So, one way of setting up better expectations for the day is to use the first minutes in the water to run some measurements on those conditions and come up with a plan for how to use those daily numbers to set some improvement goals for your practice this day.

For example, you come to the sea and find the wind is blowing to the west and that means you will have a head-on wind-driven current while you swim to the first point, a side current while swimming to the next, and a tail-current pushing you as you come back to the starting point. You cannot easily compare stroke counts or performance between the three sides of this route, but the first time around you can count strokes and set some expectations for improvement unique to each side of that route.

Or, let’s say you come to the sea and there are waves today, but you normally don’t swim with waves. They may be stressful and straining on the body, more than you are used to. You can adjust your practice plan to remove the agenda that requires smooth water and pick up the task to work on a skill you need for improving your competence and confidence in wavy water.

Rather than set a certain time requirement to swim the route in wavy conditions, you simply set the goal of achieving the distance peacefully, at any pace required by those conditions. And in achieving that, you will in fact leave the water a better swimmer than the one who entered – one with more experience, more skill, more confidence.

And that is a successful practice that takes into account the realities of each unique day.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Gear, Tempo

The Tempo Trainer (TT) is a wonderful tool for training our stroke timing, just as a musician would use a metronome to train the rhythm for a certain song. But the musicians in a band or in an orchestra don’t use their metronomes in the concert. They have practiced with a metronome enough and then weaned off of it in such a way that this sense of timing is now burned deeply into their nervous system. They don’t need that metronome other than to check in and tune up their sense of rhythm, or to learn a new song, or an old song at a different tempo.

Likewise, we train with Tempo Trainers in order to no longer need them. And, for those who participate in certain sanctioned races, they are not allowed anyway. The point of using a device like this is to train our own brain with that skill, rather than use the device to replace our brain’s skill. We use the TT in such a way to eventually learn to keep timing without one BEEPing in our ear. I call this process ‘weaning’ off the TT, like a baby eventually weans off breast-feeding.

The process of weaning off the TT is simple to explain: at first, you regularly train with the TT BEEPing on every arm stroke. After a period of time imprinting certain range of tempos you that intend to use for your event, you then set the TT to skip BEEPS (set it at 2x the rate), so that you have to imagine the BEEP on every other stroke, rather than actually hear it.

If I were to use a tempo of 1.20 and want to eventually wean off it it I may follow this sequence:

- practice some weeks with TT at 1.20 (BEEP comes at each arm entry)

- practice some weeks with TT at 2.40 (BEEP comes at only right arm entry)

- practice some weeks with TT at 3.60 (BEEP comes every 3 strokes – quite tough!)

- practice some weeks with TT at 4.80 (BEEP comes every other right arm entry)

Your brain learns to anticipate the ‘silent’ strokes between beeps, until you don’t need the TT anymore to hold perfect timing. After this, you can use Stroke Count Intervals and a memorized time chart to check your tempo during swims (explained below).

An Example Of Weaning

Ricardo has been practicing to hold a cruising pace stroke at 1.25 seconds. This means the TT BEEPs for every arm stroke at 1.25 seconds. For the next phase of TT training, he slows the TT down to 2.50 seconds and then synchronizes just one arm to coincide with that BEEP – the arms must still move at 1.25 tempo, but only one arm gets a BEEP. The other arm has to hit it’s timing in silence, but in time the brain will anticipate and fill in that gap, and Ricardo will be able to hold the tempo with 50% less frequent BEEPs. On the first interval he synchronizes the left arm to the beep and on the next interval he synchronizes the right arm, in order to balance the effect on each arm.

To go further, Ricardo then sets the TT to 5.00 seconds and then synchronizes just one arm to coincide every other stroke – so there is a BEEP-stroke, then silent-stroke, silent-stroke, silent-stroke, BEEP-stroke. This is just like the 4-beat of many songs.

I have tried it with the TT set to every third stroke (to BEEP at 3.75 seconds in Ricardo’s case) and it is a very challenging timing interval. One could find some utility for this 3-stroke TT setting (like for bi-laterial breathing), but I think its value is limited. 4-stroke time gap seems to be the next reasonable frequency.

Final Wean

One can take it even further to set the TT at 10.00 seconds (every 8th stroke). But I think once you’ve got a good rhythm at 4-stroke interval you can practice turning the TT off altogether. At that point your brain can either fill in the gaps for the three silent-strokes or it cannot.

Next, if you are in the pool, you can calculate the number of seconds, and number of strokes you will need to reach the other wall, and set the TT to this number of seconds. Then push-off the wall on the first BEEP and follow your memorized sense of tempo with stroke counting, to see if you can touch the other wall at the moment of the next BEEP. This is a nice exercise, but if you get off count, you have to go off tempo for a while in the next length to re-align and you won’t know if you’ve come close until you get to the next wall.

Occasional Checkups

A great way to further imprint your own sense of tempo is to do continuous swimming with your own sense of tempo, and then periodically turn on the Tempo Trainer to check if your sense is accurate, and then make adjustments in your perception.

For example, if I wanted to test or challenge my sense of tempo at 1.20 seconds over a 1000 swim, I could preset my Tempo Trainer to 1.20 then turn it off and stick it into my swim cap. I would swim 150, then reach up quickly to touch the button on my TT to turn it on and immediately start another 50 to compare the TT BEEP to the sense of tempo I was just swimming with. I would repeat this 5 times, stopping briefly only to quickly turn off/on the TT.

- 5 rounds of 150 without TT and 50 with TT – swim continuously

Monitoring Tempo in Open Water

In open water, my preferred way to monitor my memorized tempo is to touch the split button on my watch, count strokes to a certain number (I usually count 300 strokes) and then quickly look at the time split on my watch to see how many minutes and seconds went by.

I use this equation: Stroke Count x Tempo = Total Seconds

Here is my tempo-time chart based on 300-stroke intervals:

- 300 strokes at 0.95 tempo = 4 minutes, 45 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.00 tempo = 5 minutes, 00 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.05 tempo = 5 minutes, 15 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.10 tempo = 5 minutes, 30 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.05 tempo = 5 minutes, 45 seconds

For various reasons I have settled into using 300-stroke intervals as a standard unit of distance and time estimate for open water swimming. Every 300 strokes I know I travel roughly 300m and about 5 minutes has passed. I can then be in the middle of a swim and if curious about my tempo, hit my split button, count off 300 strokes, and then glance at my split to see a ‘close-enough’ reading of my average tempo over the last 5 minutes or so.

This has become for me a quite reliable and useful way to monitor tempo without a Tempo Trainer.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Gear, Open Water

A Tempo Trainer is an essential piece of most of our training plans.

And, for open water swimming with a Tempo Trainer, I want to urge you to practice and master this one skill: learn to click the buttons on the TT without removing it from your swim cap.

This has two main advantages:

- You do not risk losing it in the water.

- You save a lot of time during variable tempo intervals by clicking it in place, versus removing it, clicking it, and putting it back.

For race training, there are no ‘rest’ moments given in the race. So, when practicing race simulation with stroke count intervals in open water, you can hold Skate position, reach a hand up to feel the buttons, and click it in just a few seconds, and quickly resume your swimming with a minimal disruption to body position or momentum.

Instructions

Pre-set the Tempo Trainer to the setting you intend to start with. Turn it off, if you will not use it immediately.

Place the TT under the swim cap toward the back of your head, behind the ear, where you can reach it with your dominant (writing) hand. Make sure the cap completely covers the TT and comes back snugly upon your skin or hair. Make sure the two TT buttons are at the bottom and then check to assure yourself that you can feel with your fingertips both the left and the right button through the swim cap.

Practice turning on the TT by pressing the right button for 1 second and practice turning it off by pressing down on both buttons at the same time.

[In Mode 1] Practice clicking the TT faster by 0.01 second pressing the left button, and practice clicking the TT slower by 0.01 second pressing the right button. In the practice sets of this training plan you will be adjusting tempo only by 0.03 seconds (3 clicks) between any two repeats – so not enough to forget your click amount in the midst of a demanding interval set.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Tempo

Before choosing a suitable tempo you first need to have established an suitable stroke per length (SPL) for your purposes. Then you can consider what tempo is appropriate with that SPL, and how much expansion you will need in your tempo range to be able maintain that SPL x Tempo combination.

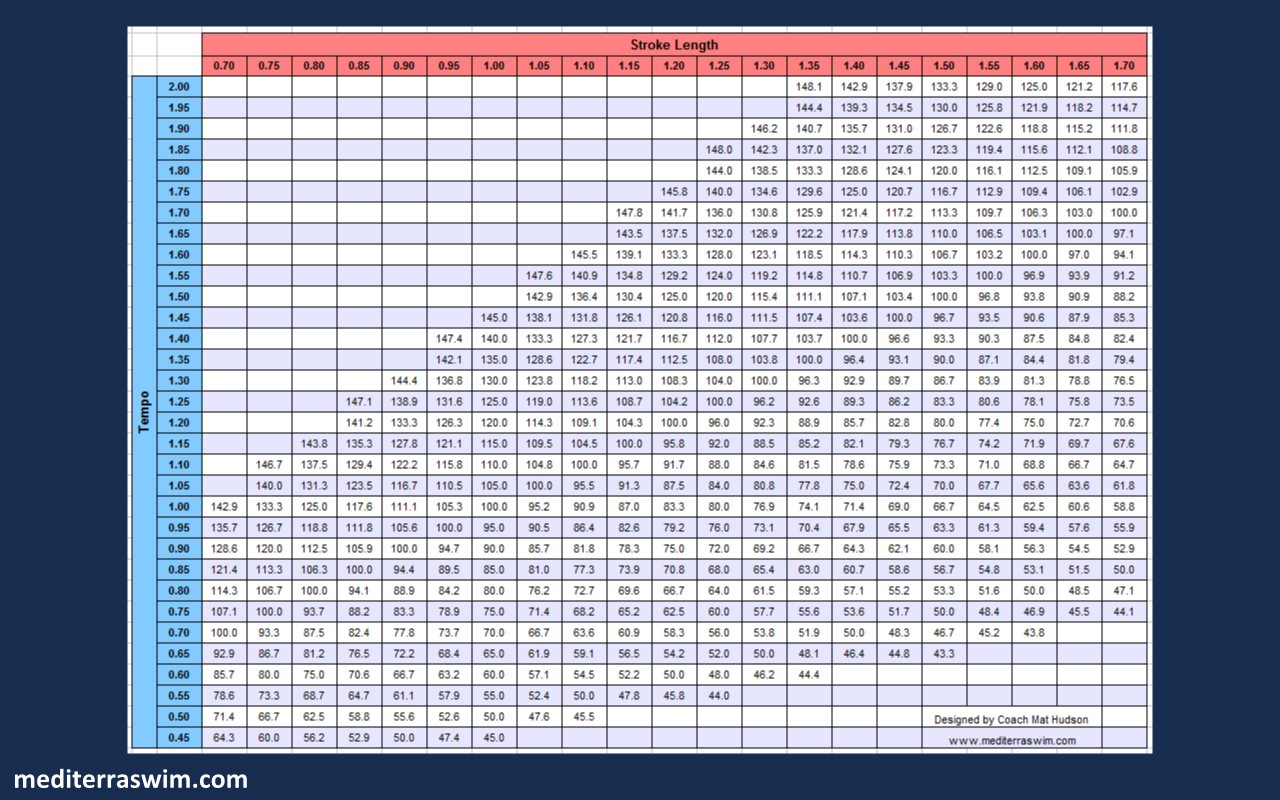

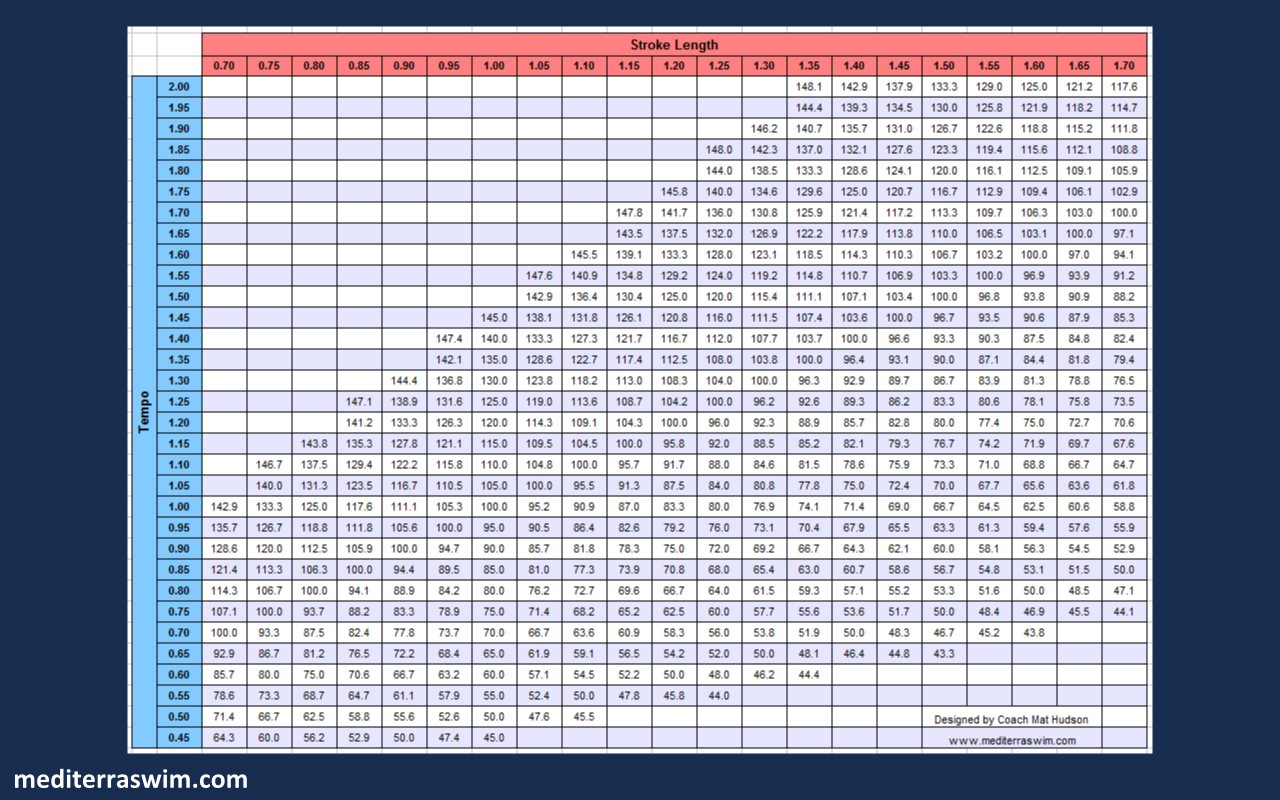

You may view these charts to get some idea of what pace is produced by various SPL x Tempo combinations:

As you increase tempo you will be challenged to maintain SPL consistently. Tempo control adds another level of complexity for the brain. When you are new to tempo control, while focused on holding your stroke to the beep, if your SPL count goes (too high) out of your optimal stroke count, or Green Zone, likely something fell apart in your technique. If you are using an SPL lower than your Green Zone, you may likely find it more difficult to achieve higher Tempos – there is a critical relationship between your ideal SPL and your ideal Tempo. It gets harder, if not impossible to work at either extreme.

Your goal is to keep your SPL in the Green Zone, while working to gradually increase the Tempo you can maintain inside that Green Zone, and work on this in short repeats. You will first work on being successful in short lengths before expecting to be successful on several uninterrupted lengths.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Metrics

This chart shows Stroke Length x Tempo combinations to create Pace for 100 meters (in seconds). This chart is intended for open-water (no walls, no flip-turns or interruptions to the stroke), therefore

Pace = (100m/SL) x Tempo

For example: Maria uses a Stroke Length of 1.05 (red numbers, vertical column) and a Tempo of 1.10 seconds per stroke (blue numbers, horizontal row) to create a Pace of 104.8 seconds or 1 minute 44.8 seconds per 100 meters.

To convert your pool SPL into universal Stroke Length number:

Pool Length – Glide Distance = Swim Distance

Swim Distance / SPL = SL

For example:

Maria swims in a 25 meter pool. She glides 5 meters from the wall to begin her first stroke #0. She has an average SPL of 19.

25m – 5m = 20m Swim Distance

20m / 19 SPL = 1.05 meters per stroke.

**

Keep in mind that if you are training to achieve a certain Pace for open-water swimming, you need to train for that Pace. The speed of flip-turns and push-offs in the pool affect the Pace equation. The distance you actually swim (take strokes) in the pool is what is training you for that open-water event, not the flip-turns and push-offs. So I recommend that you pick your SL (SPL) x Tempo combination based on the setting (pool or open-water) that you are preparing to race in.