by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Gear, Open Water, Tempo

Ideally, you would work with a Tempo Trainer to train the brain to hold a consistent tempo, or with a specific range of tempos, so that eventually you no longer need a Tempo Trainer to stay on tempo. There may be many situations – especially in racing open water, triathlon and masters pool meets – where a TT may not be allowed, or desired.

So, there is a process you go through for training your sense of tempo with the TT, and then a process for weaning yourself from the TT so that you don’t need it so much any more.

However, like a lot of delicate measuring equipment, even if you’ve gone through a rigorous process of burning certain tempos into it, your brain still needs occasional tune up of its sense of tempo to keep it accurate – like a guitar needs a occasional tuning.

One way to test and train your sense of tempo is to preset your Tempo Trainer to your desired tempo, turn it off and then slip it into your swim cap. Go for a longer swim set or a long continuous swim and then at regular intervals, turn it on for short periods of time to check how close your sense of tempo is to the precise tempo on the TT.

Example In The Pool

First swim 100 at your chosen tempo with the TT turned on.

Then swim 5 rounds of 200.

Start each 200 with the TT turned off and only your sense of tempo to guide you. One the last 50 of each 200, turn on the tempo trainer to see how close your perception is to the accurate tempo of the TT.

Example In Open Water

Swim 2 minutes at your chosen tempo with the TT turned on.

Then swim 5 rounds of 200 strokes, which may be around 1000 plus or minus.

Start each 200 with the TT turned off and only your sense of tempo to guide you. One the last 50 strokes of each 200, turn on the tempo trainer to see how close your perception is to the accurate tempo of the TT.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Gear, Tempo

The Tempo Trainer (TT) is a wonderful tool for training our stroke timing, just as a musician would use a metronome to train the rhythm for a certain song. But the musicians in a band or in an orchestra don’t use their metronomes in the concert. They have practiced with a metronome enough and then weaned off of it in such a way that this sense of timing is now burned deeply into their nervous system. They don’t need that metronome other than to check in and tune up their sense of rhythm, or to learn a new song, or an old song at a different tempo.

Likewise, we train with Tempo Trainers in order to no longer need them. And, for those who participate in certain sanctioned races, they are not allowed anyway. The point of using a device like this is to train our own brain with that skill, rather than use the device to replace our brain’s skill. We use the TT in such a way to eventually learn to keep timing without one BEEPing in our ear. I call this process ‘weaning’ off the TT, like a baby eventually weans off breast-feeding.

The process of weaning off the TT is simple to explain: at first, you regularly train with the TT BEEPing on every arm stroke. After a period of time imprinting certain range of tempos you that intend to use for your event, you then set the TT to skip BEEPS (set it at 2x the rate), so that you have to imagine the BEEP on every other stroke, rather than actually hear it.

If I were to use a tempo of 1.20 and want to eventually wean off it it I may follow this sequence:

- practice some weeks with TT at 1.20 (BEEP comes at each arm entry)

- practice some weeks with TT at 2.40 (BEEP comes at only right arm entry)

- practice some weeks with TT at 3.60 (BEEP comes every 3 strokes – quite tough!)

- practice some weeks with TT at 4.80 (BEEP comes every other right arm entry)

Your brain learns to anticipate the ‘silent’ strokes between beeps, until you don’t need the TT anymore to hold perfect timing. After this, you can use Stroke Count Intervals and a memorized time chart to check your tempo during swims (explained below).

An Example Of Weaning

Ricardo has been practicing to hold a cruising pace stroke at 1.25 seconds. This means the TT BEEPs for every arm stroke at 1.25 seconds. For the next phase of TT training, he slows the TT down to 2.50 seconds and then synchronizes just one arm to coincide with that BEEP – the arms must still move at 1.25 tempo, but only one arm gets a BEEP. The other arm has to hit it’s timing in silence, but in time the brain will anticipate and fill in that gap, and Ricardo will be able to hold the tempo with 50% less frequent BEEPs. On the first interval he synchronizes the left arm to the beep and on the next interval he synchronizes the right arm, in order to balance the effect on each arm.

To go further, Ricardo then sets the TT to 5.00 seconds and then synchronizes just one arm to coincide every other stroke – so there is a BEEP-stroke, then silent-stroke, silent-stroke, silent-stroke, BEEP-stroke. This is just like the 4-beat of many songs.

I have tried it with the TT set to every third stroke (to BEEP at 3.75 seconds in Ricardo’s case) and it is a very challenging timing interval. One could find some utility for this 3-stroke TT setting (like for bi-laterial breathing), but I think its value is limited. 4-stroke time gap seems to be the next reasonable frequency.

Final Wean

One can take it even further to set the TT at 10.00 seconds (every 8th stroke). But I think once you’ve got a good rhythm at 4-stroke interval you can practice turning the TT off altogether. At that point your brain can either fill in the gaps for the three silent-strokes or it cannot.

Next, if you are in the pool, you can calculate the number of seconds, and number of strokes you will need to reach the other wall, and set the TT to this number of seconds. Then push-off the wall on the first BEEP and follow your memorized sense of tempo with stroke counting, to see if you can touch the other wall at the moment of the next BEEP. This is a nice exercise, but if you get off count, you have to go off tempo for a while in the next length to re-align and you won’t know if you’ve come close until you get to the next wall.

Occasional Checkups

A great way to further imprint your own sense of tempo is to do continuous swimming with your own sense of tempo, and then periodically turn on the Tempo Trainer to check if your sense is accurate, and then make adjustments in your perception.

For example, if I wanted to test or challenge my sense of tempo at 1.20 seconds over a 1000 swim, I could preset my Tempo Trainer to 1.20 then turn it off and stick it into my swim cap. I would swim 150, then reach up quickly to touch the button on my TT to turn it on and immediately start another 50 to compare the TT BEEP to the sense of tempo I was just swimming with. I would repeat this 5 times, stopping briefly only to quickly turn off/on the TT.

- 5 rounds of 150 without TT and 50 with TT – swim continuously

Monitoring Tempo in Open Water

In open water, my preferred way to monitor my memorized tempo is to touch the split button on my watch, count strokes to a certain number (I usually count 300 strokes) and then quickly look at the time split on my watch to see how many minutes and seconds went by.

I use this equation: Stroke Count x Tempo = Total Seconds

Here is my tempo-time chart based on 300-stroke intervals:

- 300 strokes at 0.95 tempo = 4 minutes, 45 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.00 tempo = 5 minutes, 00 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.05 tempo = 5 minutes, 15 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.10 tempo = 5 minutes, 30 seconds

- 300 strokes at 1.05 tempo = 5 minutes, 45 seconds

For various reasons I have settled into using 300-stroke intervals as a standard unit of distance and time estimate for open water swimming. Every 300 strokes I know I travel roughly 300m and about 5 minutes has passed. I can then be in the middle of a swim and if curious about my tempo, hit my split button, count off 300 strokes, and then glance at my split to see a ‘close-enough’ reading of my average tempo over the last 5 minutes or so.

This has become for me a quite reliable and useful way to monitor tempo without a Tempo Trainer.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Gear

Let us introduce you to the Finis Tempo Trainer Pro. It is a waterproof metronome for swimming. You turn it on, place it under your swim cap or one a clip attached to your goggle strap. It creates a BEEP sound on the interval that you set with the buttons – that BEEP is beeping like seconds on a watch, and you control how many seconds there are between those BEEPs.

This is small, but extremely useful device. We would say it would be the most important part of your training gear after after your suit and goggles.

Coordinating The BEEP

In the most simple use of the Tempo Trainer Pro, you simply coordinate the movement of your stroke with the BEEP. You can coordinate that beep with any part of the stroke you want, anywhere on the body.

You could concentrate on timing the beep with one of these easily identifiable points in the freestyle stroke:

- The fingers of your spearing hand cut the surface of the water in front

- Your lead arm reaching full extension point

- Setting the catch

- Initiating the torso rotation

- The timing of the kick

The Tempo Trainer can be used for the other three competitive stroke styles, but it gets complicated when doing it with butterfly and breaststroke so we recommend you get skilled at using it on freestyle or backstroke before trying it on the others.

Tempo Trainer Instructions

You may want to view the official Finis Tempo Trainer Manual (pdf download).

You may want to view the official Finis Tempo Trainer Manual (pdf download).

On the Tempo Trainer Pro there are three modes it can be set to. When you depress the top button for 2 seconds, it toggles between Mode 1, 2 and 3.

For most of our training assignments in the Dojo and in live training we use Mode 1, which works in ‘seconds per stroke’. Mode 2 can be set for longer intervals, such as the seconds per length or lap, so that you can try to come to the wall on the BEEP. Mode 3 is an inverse of Mode 1, and works in units of ‘strokes per minute’ (SPM) – this is more useful for open water swimming, or is preferred by those who think more in terms of SPM.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Gear

Can I or should I wear a swim cap?

The short answer: Maybe.

If the facility requires all swimmers to wear a cap, then yes, wear one. In the USA it is not common for pools to require this. In Europe it is common for pools to require every to wear a swim cap.

If you have hair long enough to get in your face, then it can be very helpful, especially in swim lessons, to wear a swim cap to keep it all contained and out of the way.

If you are concerned about pool chemicals damaging your hair, or if you are easily chilled in the water, then the swim cap can provide a little help insulation against that, but certainly not complete.

The swim cap reduces some of the surface drag around the head, so it may be slightly more streamline to wear one.

But if you don’t feel the need for a swim cap, you may go without. The water flowing against the nerve receptors on the skin of your head is one more area of sensory information that can help you in your proprioception!

You may read more about Hair Care for The Pool.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Gear

Every human face is different, and therefore the way swim goggles fit will be different. Finding a pair that suits you is a trial-and-error process.

And different kinds of goggles may work better for different kinds of swimming situations. For racing in the pool, many people prefer slim, compact goggles that fit within the eye sockets. For swimming in open water (or being in the water for hours) many people prefer the kind that seal around the eye brows and eye sockets, almost like a snorkel mask.

When searching for a pair, most stores seem to be OK with you taking them out of the box to try them on. It won’t be the same as testing them in the water, but you can still feel how well it seals and fits.

If you are trying on the eye-socket type goggles, raise your eye brows and open your eyes wide, then place the goggles in the eye socket and relax the face so that the skin around your eyes squeezes around the outside of the goggle gasket. Press the goggles until you hear or feel a suction.

If you are trying on the mask type goggles, relax your face and smooth your brow then press the goggles onto your face. Press the goggles until you hear or feel a suction.

The goggles should create a suction on your face without the need for the strap to be holding them tight against your head. As a matter of fact, the less tension needed in the strap the better. If the suction only holds while the strap is pulling them tightly against the head then this is a sign they won’t work well for you.

Once they are securely affixed, make many different expressions on your face that will cause your cheeks, eyes, brow and nose to reshape your skin and face, which could affect the seal of the goggles. Move your face around, make faces, squint, crinkle your nose, close one eye and then the other. you want to make sure the seal doesn’t pop. Next check the bridge of the nose and corner of eyes for any gaps or discomfort.

There should be some suction pressure inside the goggles – that is normal. If they don’t pinch the skin, or rub the bridge of the nose, or hurt in any particular spot, then you may have a winner. Make sure to check return policies, just in case the pair isn’t what you expect when trying it in the water.

And, when you find a pair you really like, you may consider buying a few of them at once so that you have a small stock of them. It is sad when we find a pair we really like then, when we need to replace them, we find out the manufacturer has discontinued making that model and they are hard to find. We have to go through this whole process all over again.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Gear

Can I or should I use hand paddles?

With every training device we recommend that you apply some basic principles. You can read more about this in Guidelines for Using Swim Training Devices.

The short answer is: No.

There is possibly a way to train with hand paddles that would allow the swimmer to carefully train the connections through the body and activate muscles in a certain pattern without putting undo strain in the shoulder joint, but we never see anyone using them this way. Paddles seem to overwhelmingly urge swimmers to pull on the water in a way that is de-training the kind of whole body connection we are working so hard to establish. Paddles focus attention on the hand, and load the shoulder joint with a torque. That emphasis on the hand places a greatly increased amount of force on the end of the arm, the end of the lever, which means a great deal of torquing force is created inside the shoulder joint which increases the risk of injury.

We want to distribute the load up the forearm, brace the shoulder joint and use the torso rotation to empower the stroke. Paddles make it harder to do this.

Instead we recommend…

Use Fist Swimming Instead

Until you are a master of catch timing we highly recommend the use of fist-swimming instead – make the hands smaller rather than larger, and your brain will be forced to find a better grip on the water using the entire forearm. This will require you to lift the elbow and keep the hand below it and maintain the forearms grip on the water – since the small area the fist by itself can no longer do the work for you.

After all, you are preparing to do what? To swim a race with paddles on? (Granted, you can in the Ötillö, and that is a pretty cool race!) Or must you use what your body naturally comes with to get the job done?

Learn to use what you’ve got better, and continually train the brain to use all the piece working together. Use the forearm as much as the hand, and empower the catch with the torso rotation – fist swimming will urge you in this direction while paddles will urge you away from it.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Gear

Can I or should I use a nose clip?

The short answer is: Maybe.

You may use a nose clip if you are dealing with strong allergies to chlorine or pool chemicals. Keep in mind that everyone is irritated by the chlorine and have learned to tolerate it. After being away from the pool for some time even an experienced swimmer may feel increased sensitivity to it.

You may use a nose clip early on in your learning process if water going up your nose triggers strong anxiety and interferes with your learning process. Your brain is trying to keep you safe from what it perceives as a danger, after all. However, water going up the nose is a common experience for all swimmers and they learn to tolerate it. Although it is uncomfortable, it is not, in fact, dangerous. However, it does take time and a gradual, gentle exposure process to get your brain to calm down and no longer be alarmed by water going up the nose and the burning sensation in the sinuses. The better you get with the fundamental breathing skills the less you will have that happen to you. The more it happens to you and nothing dangerous actually takes place, the more your brain will normalize the experience and reduce the alarms you experience.

If you are determined to master the breathing skills, the more you need to set that nose clip aside and work on them. The control over the inflow and outflow with the nose is a central piece of the whole breathing skill set.

You can always bring your nose clip to the pool and try using it and not using it for part of the time. You may gradually wean yourself off of needing it.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Gear

Can I or should I use fins?

With every training device we recommend that you apply some basic principles. You can read more about this in Guidelines for Using Swim Training Devices.

The short answer is: Yes, you may use a snorkel in limited amounts, for certain purposes.

Fins can be helpful to provide a little propulsion from the legs when you are working on holding streamline position or working on the choreography of the torso and arms in slower motion (when those slow actions will not provide much consistent propulsion).

We would recommend using shorter ‘zoomer’ or swimmer type fins, not the longer diving or recreational fins. The swimmer fins allow a faster, more swimmer-like spacing of the feet, tempo of motion and flex of the ankles. If you are looking for a recommendation, we like to use the Finis Postive Drive fins, these allow you to keep the feet closer together and move them more like you would when kicking without fins on.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Gear

Can I or should I use a kickboard?

With every training device we recommend that you apply some basic principles. You can read more about this in Guidelines for Using Swim Training Devices.

The short answer is: No, do not use a kickboard.

The use of a kickboard for kicking activities creates new problems as much as it tries to help with fitness. We consider it a significant liability to your spine and your swimming form. This is not just our opinion, but a growing consensus among experts in swimming biomechanics.

If you would like to do kicking sets, we recommend that you do not use a board, but instead get into the actual streamline position for that stroke and kick in that position, as close to the posture in which you will use the kick in its context. This may mean you need to use a snorkel to breath so that you can maintain that position for longer uninterrupted periods of time.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 21, 2020 | Gear

Training devices are extremely popular among swimmers and triathletes – with new fads coming each year – and people are looking to their coach to have an opinion on these. Unfortunately, very few can offer explanation beyond the product’s marketing hype to back their opinion with substantial logic or sound scientific explanation.

But with any training device, if you understand what the tool can help you with, what it’s role in the skill-development process is, and what it’s liabilities are, then you are in a better position to choose when to use it or not.

These considerations apply to various swim training tools you see others using or might consider using for yourself like snorkels, fins, paddles, boards, etc. Rather than give you unqualified encouragement to use anything you see, I want to urge you to think critically about the device’s stated purpose (think past the marketing surrounding it), then seek out some understanding or guidance on how you’ll get the best benefit out of it, according to your particular needs and goals.

To help in moving beyond that marketing hype and chaos of opinion, let me share some general guideline I use that may help you also when thinking about using any swim training device.

Enhance Skill, Rather Than Replace It

An overarching principle is to use devices that provoke your own brain and body to get stronger, smarter, to increase it’s skill in perception and control, to ultimately do better without the device. This is in contrast to using a device that overrides and replaces your skill, ultimately making your own brain and body less capable without that device.

Example

Using a Tempo Trainer to train your brain to execute the stroke choreography with precision, within a fixed time interval, is powerful. But eventually, you need to train in such a way to imprint that sense of tempo into the brain and wean yourself off the Tempo Trainer so that it is no longer necessary.

Improve Attention

The device should help you turn away from distractions so you can devote better attention to work on some part of your body or stroke. If you have two skills that need work, but you cannot easily work on both at the same time, an assisting device may allow you to set aside concern for one of them while you focus on the other.

Example

A swimmer snorkel can allow you to turn off the need to turn to breath so that you take more consecutive strokes without interruption.

A swimmer may use a Tempo Trainer to draw attention to a particular moment of the stroke that is timed to the BEEP.

In contrast, a waterproof MP3 player could be loaded with songs that keep your stroke moving at certain desired tempos. While it could also cause you to tune out of what’s happening in your stroke, allowing you to tolerate inferior movement patterns, less than your best.

No Interference

While working on one particular skill that device should does not interfere with another critical piece of the stroke that your skill project is dependent on.

Example

A pull buoy is most commonly used to lift up sinking hips, so the swimmer can enjoy swimming parallel to the surface. But the skill of swimming parallel to the surface requires that the swimmer build a tensile frame through core of the body (including the pelvis and thighs) and then send water flowing under this frame to give it lift. But a pull buoy artificially supports and replaces the core’s role causing it to collapse and disconnect from the front of the body. Whatever patterns the swimmer is training with the upper body while pulling with a buoy is not disconnected from its essential relationship to the core. There is virtually no situation I can think of where this is a good idea in the long-view of swimmer development.

Swimmer fins can be useful temporarily to allow the swimmer to focus on the upper half of the stroke, moving in slow-motion, carefully etching the movement patterns, while the fins, moving gently, provide some lift to the legs. Or while in streamline position, one can stay in streamline position with flow of water along the body line offering feedback on how well he is reducing drag with each adjustment in shape. With fins, unlike the pull buoy, while still providing some lift to the lower body, they still allow if not urge the swimmer to engage the core to self-support the middle zone of the body.

No New Problems

In helping solve one skill problem, the device should not create a new problem or bad habit that you must spend additional time breaking.

Example

I think there could be a good way to use them, but in the way that they are typically used to build more shoulder and arm muscle strength hand paddles are actually training an inferior movement pattern, training the swimmer to load smaller shoulder muscle group rather than the larger, longer-lasting torso muscles. And used that way, they greatly increase the stress inside the shoulder joint.

You will do much better using Fist Swimming, the anti-paddle. which forces you to build pressure along the wrist as much as the palm, lowers stress at the shoulder joint, and gives you a more easily recognized opportunity to tap into the torso muscles. Fist swimming is a wonderful example of super-charged, self-limiting practice principle (and some ideas for other self-limiting practice sets).

Remove Dependencies

Other than temporarily, you should not use a device to cover up and avoid dealing with a weakness in your skill. If you keep developing your strengths and avoid dealing with your weaknesses, you will increase the disproportions in skill and strength which will set you up for greater risk of injury and hinder your progress. The farther away your weaknesses become from your strengths, the more frustration you may experience when you are eventually forced to work on those. Or those neglected weaknesses will result in injury which will shut you down.

Example

Buoyancy shorts might be helpful while working on slow drill work, but at some point the swimmer has to learn to keep his body near the surface through skilled control of your body. The buoyancy removes the consequence, it removes the feedback that would otherwise force one to learn how to balance his body and keep it flowing near the surface. This balance is a skill accessible to nearly every human body when trained how to do it. Otherwise, he may never be comfortable swimming without them.

Perhaps he is training to race in open water with a wetsuit and so training with buoyancy shorts in the pool seems inconsequential. But the core engagement, the internal frame of the body that is used for more than just to create lift – it is also the center through which force is transferred through the body.

The immediate ease of using buoyancy shorts may tempt one away from going through the longer, patient process of finally developing that internal frame of the body which would benefit performance in more than just reducing drag from a sinking tail.

Know How To Use It, And How Not To Use It

With any tool, it’s effectiveness depends on how well one uses it to imprint the skill into the brain while removing the need for the tool, and without causing new problems.

Inventors (we love them!) are constantly trying out new ideas on us swimmers, to solve what other health practitioners recognize as neural or neuro-muscular problems, whether the inventor or users recognized that or not. The inventor see the market possibilities, and may leave it up to coaches or swimmers to figure out the best way to use them – it’s not a bad way of crowd-testing these clever ideas, but it certainly has its risks for swimmers who don’t know any better.

When a new tool comes along, we can’t simply see others using it and make that the reason to use it ourselves. We need to consider its actual intended purpose and misuses, to consider how that device can be used safely and how it might be used unsafely. We need to consider the process we should follow to move from dependence on the device for control of the body to dependence on the brain for control of the body. We need to know how to use it in such a way to avoid creating new problems along the way. Except in the case of adaptive equipment for permanently disabled athletes we generally want to use devices in order to eventually leave those devices behind.

The devices may not be to blame for poor skill development, while the lack of a thoughtful brain-training process likely is. Too often these devices are used without understanding of how complex neuro-muscular skills are developed and imprinted into the brain (often without much help from the way in which this device was marketed), and just hope that by using it like everyone else is that this new skill will magically happen. Nope. It doesn’t work that way.

Good devices don’t create strong skill; good processes with good focus do. Sometimes a device or tool might assist with that process, and sometimes it will interfere.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 21, 2020 | Gear

Can or should I use a snorkel?

With every training device we recommend that you apply some basic principles. You can read more about this in Guidelines for Using Swim Training Devices.

The short answer is: Yes, you may use a snorkel in limited amounts, for certain purposes.

A snorkel made for swimmers is a good tool to remove the concern for turn-to-breath, when used for short periods of time. If breathing is yet disruptive to body position or distracting to the mind in some significant way, then using a snorkel can allow you to set aside this problem for short periods of time to work on some other feature of the stroke. Then set aside the snorkel to work on breathing.

Breathing is an urgently needed skill, but that doesn’t change the fact that it is an advanced skill that is dependent on foundation skills. The stronger the foundation skills the easier it will be to establish smooth, easy breathing, and vice versa. That’s just one of the reasons that in Total Immersion we are so adamant about your patience in setting up those fundamental body positions and movement patterns. But we also introduce breathing skills within Level 1 training… at the end, once you can lean upon those foundation skills to make breathing easier to do.

If you are going to use one we may recommend the Finis Swimmer’s Snorkel, just like this one pictured. Specifically called a ‘swimmer snorkel’ – one that is positioned on the front of the face rather than to the side.

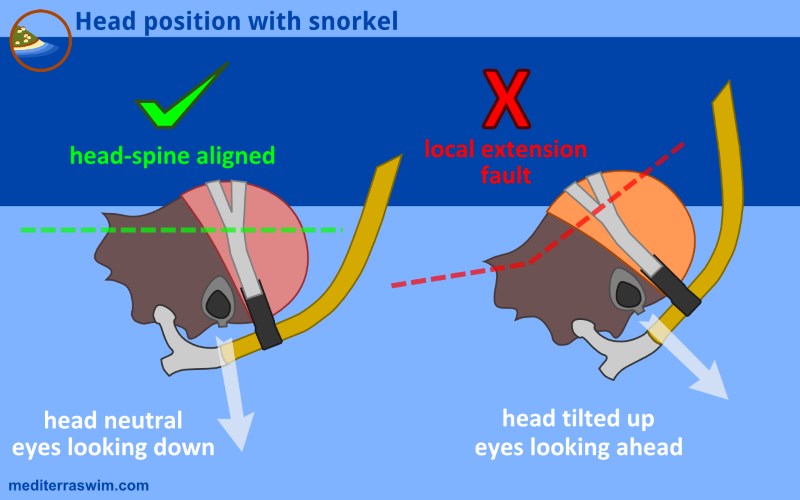

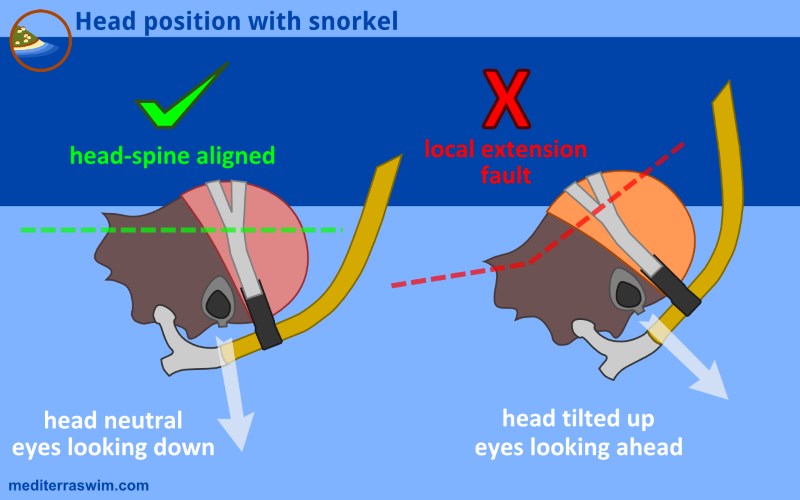

One liability is that the snorkel has that small volume of air in the tube in front of your mouth that you have to hold underwater if you want your face underwater, and it pushes back on your face, urging your neck into a local extension fault (i.e. tilting the head, putting a local bend in the cervical spine, to look ahead). There’s no way to avoid this push-against-the-head even with your head in neutral – it’s just water pressure pushing up on the air space in the tube. If you are trained and loyal to a neutral head-spine position (as you should be as a TI swimmer), then this will put a strain on the neck with that air pocket trying to push your head up and out of neutral position. You’ll feel the difference within a couple minutes and may likely find it unpleasant, from the neck or even down to the low back.

The whole body follows the head position, so anytime the head is out of this neutral position, realize that the rest of the spine will have a hard time finding or staying in its ideal balance and alignment. Therefore, one would want to use a snorkel sparingly to avoid this strain.

Obviously, many conventional swimmers seem to adapt to that head position with or without a snorkel and claim no problems, but with a tilt-down of the head into neutral position we’ve quickly fixed too many people with sore necks and sore lower backs now to encourage that tilted-up head position for anything but the shortest periods of time – as with ‘snapshot’ sighting in open water. (Discussing the use of a snorkel for other training purposes would be another topic, but the same spine health concern remains).

In conclusion, a swimmer snorkel like this is a nice tool to have in your bag to use on occasion, or to lend to a friend in the throes of stroke+breathing struggle. But if you are going to use one for this purpose, I strongly recommend that you spend at least as much time in that practice working on improving your breathing skills (correcting head position, timing, and air management) so that the breathing problem and subsequent need for the snorkel is eventually removed. Then you may consider using it for other purposes – but please employ the same critical thinking process before you do.

It’s important not to hide behind the snorkel to avoid working on the aspects of breathing that are still difficult for you. Use it in limited amounts to work on other skill projects and then come back to your work on breathing.

You may want to view the official Finis

You may want to view the official Finis