By the end of a series of live lessons in Level 1 I hope to have a chance to introduce you to the synchronization of the propulsive pieces of your stroke. Up to that point you have worked on shaping the individual sections of body position and movement patterns, and this is where you connect a few of them together to feel their combined effect. It is usually a surprising and thrilling experience because you can feel how force flows through your body more smoothly and with much better effect on how fast and far you travel on each stroke.

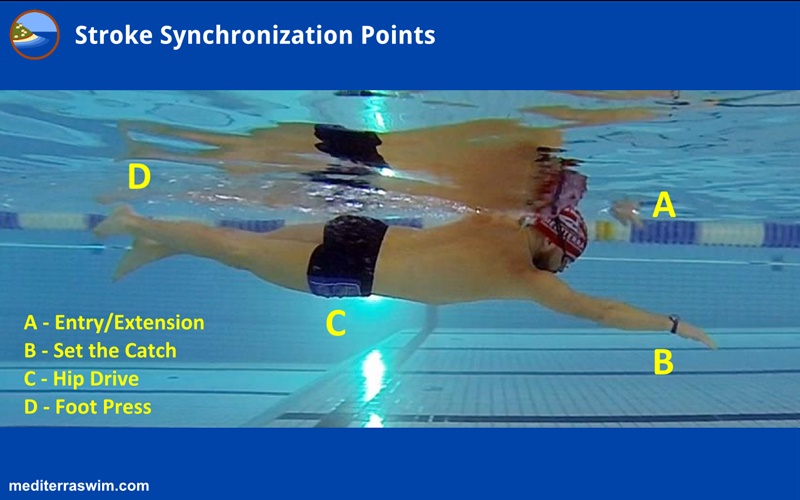

Here are the four main points of the body we look at for synchronization:

A is at that moment right when the finger tips pierce the water to begin the entry.

B is at that moment that your hand and forearm curve to ‘touch the ball’, and set the catch, just before you actually start to put pressure on the catch.

C is at that moment the torso starts to turn.

D is at that moment the upper (Skate side) foot begins to press down.

Synchronization practice involves a combination of any two of these points, to examine how they work together and then to fine tune their synchronized timing. You can work at combining AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, and CD.

All four points are doing something at about the same moment, but it is nearly impossible to concentrate on all four of them at once. So it is better to work on just two of them at a time, and circulate through the combinations.

AB is usually the first combination I teach you because these two are what you’ve already been focused upon in the lesson series.

Combining C with A or B is the next step because you’ve been working on hip rotation the whole time without necessarily focusing upon it in terms of propulsion – yet that rotating torso is what will make your swimming feel the most effortless – it is the key to everything! Thinking about the hip is the same thing as thinking about the torso – the hips and shoulders should be one solid torso unit, but it is easier to think of one specific point on the torso when examining the connection to the arms or legs, so we just use the hip as that point.

Using D will not really make sense until you have had some instruction on how to form a 2 Beat Kick. And trying to time the press of your foot does not work until you have first have the timing of AB worked out. So until you’ve got the timing of the arm-switch worked out and you’ve had some instruction on 2BK don’t worry about D.

Synchronization is what makes the ‘magic’ happen – the torso rotation produces the best force, and your appendages need to work in careful timing with that rotation in order to tap into and enhance that force.

Tempo Affects Fine Timing

There is not one precise timing that works best at all tempos. At different tempos, there will be slightly different timing between each part. In one tempo range two of these points might create the best effect when they happen simultaneously, while in a different tempo range one should happen a micro-second before the other in order to get the best effect.

For example, let’s look at AB.

When moving at slow and moderate tempos the fingers and wrist of your entry arm (A) may pierce the water before you set the catch (B). B happens just a micro-second after A. When moving at fast and sprint tempos, the fingertips of your entry arm may just cut into the surface as you set the catch. A and B will feel like they happen simultaneously.

Why did I put ‘slow’ in quotes? Because you currently have a range of comfortable tempo and what feels slow and fast to you may not be the same for someone else. If you have been using a Tempo Trainer and have some idea where your current comfortable range is, you may look at this scale to get an idea where your tempo range fits within the way tempo is used by a consensus of swimmers.

You Should Experiment

I could give you some idea of what the fine timing should be between two points at various tempos, but I would need to ask a dozen questions to get the context of your stroke. You will do well to experiment and discover for yourself what timing works better.

Using the AB combination, start with exaggerated mis-timing on a series of 2x 25. For the first 2x 25 have A clearly happen before B. Then on the next 2x 25 reverse that, have B clearly happen before A. Then do 2x 25 where you try to make A and B happen at the exact same moment – right between those two extremes you just experienced.

Take measurements inside and outside your body to evaluate the effect of each timing arrangement. Ask yourself:

- How did it feel? Did I feel like force was stronger? Smoother?

- What did it produce? Did it make my stroke count go up or down or no change? Did it push me to use a faster tempo or slower tempo, or no change?

From your current comfortable tempo range you may pick three tempos – one on the fast end of comfortable, one on the slow end, and one right in the middle. And run this experiment at each of those tempos, in order to see how you might fine tune the timing of those two points differently at different tempos.

Swim 3 Rounds of:

- 2x 25 with A before B

- 2x 25 with B before A

- 2x 25 with AB at same moment

For each round:

- Round #1: Slow Tempo

- Round #2: Comfortable (center) Tempo

- Round #3: Fast Tempo

Run this experiment with different combinations:

- AB

- AC

- BC

Want More Practice?

I like to train for part of the year on each extreme – a few months working on 100y sprint distance and the other months on longer distance 5km+. These two extremes involve the use of a totally different range of tempos: 0.75 to 0.85 for sprints and 0.90 to 1.00 for distance. And I modify the tempo range a bit more if the water will be cooler or warmer. Each tempo range requires me to calibrate the synchronization of the stroke to what feels the best and produces the best results. Probably 90% of more of my training involves synchronization focal points, and I find it to be the most thrilling because better synchronization produces better ‘magic’.

If you would like more practice at this you may check out this practice in the library for some ideas.