by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Skill Learning

You may notice in our training plans and courses we don’t often tell you which drill to use. You need to review lesson notes and reflect on your live lesson experience to choose those which suit your needs right now.

We do not attempt to tell you what drills to use because the selection of the right drill is quite personal to your own situation. What skill do you want to work on? How simple or complex do you need the starting activity to be? How many repetitions of that drill will you need to do to get a grasp or tune up for the next activity? Those are questions that each person would answer differently.

You may be uncertain yet about which ones to use for which skills, but through experimentation you will quickly learn those which help you the most and those that do not. You may view Guidance for Working With Drills. You may ask on the forum or ask your coach for recommendations. Eventually, we hope and intend that you will have enough experience with the drills to know which to use for your learning needs in this moment.

Just ask if you need help!

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Skill Learning

In your ongoing practice of swimming you eventually come to know what your best slippery form feels like and what your best efficient stroke feels like – these sensations are subjective – and you come to know what your objective metrics should show – such as a certain pace or heart rate or stroke count.

You swimming practice is meant to work through these three tasks, in this order of priority according to physics:

- Remove or reduce the natural forces working against you

- Recruit the available natural forces that can assist you in moving forward

- Apply your own power – just the amount needed, and in the precise location and timing

Probably 90% or more of the struggles faced by common swimmers are solved by working on just the first two points above. However, it is easily observed that most swim programs seem to devote 90% of the time working on only #3, and they get far less improvement than they could because they haven’t sufficiently solved the first two points.

A Drill is a Diagnostic Tool

Drills are activities that allow you to isolate a part of the body or a part of the movement and make it easier to pay attention and control that part. Drills can also be used to help you diagnose a problem. By using a drill you can isolate a part of the body you suspect is having a problem and there you can experiment to find out what is causing that problem so you can correct it, and also notice what is working as it should so you can protect those features.

The fact that you can feel that something is wrong is a very good sign, and it is the first step to improvement. The next step is to find out exactly what it is so that you can work on it.

But there is the problem of having hundreds of details to search through in the stroke! And if you don’t have a coach there to notice immediately and bypass all that you need a way of organizing your search for the root problem. So, this is where you take up a diagnostic map and guide you in a way to use drills to test various parts of the stroke in an orderly way and help expose the weak spots.

Your Diagnostic Map

The three points above examine the problem from a physics viewpoint. Then we overlay that physics viewpoint with physiological/neurological view point to build this Diagnostic Map:

1 – Look for Frame Problems

First use a drill to scan for problems in the frame, in the connection of the upper and lower parts of the body, in the balance, and in the stability (side to side balance).

2 – Look for Streamline Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems in rotation, in connection of the streamline side of the body, in the arm or scapula position, in the position of the head or legs.

3 – Look for Stability Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems in balance when moving the recovery arm, in the lead arm, in the legs, in the rotation angle.

4 – Look for Connection Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems in the connection of the entry arm to the torso, or with the catch and the torso rotation.

5 – Look for Breathing Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems with the position of the head, the timing of the turn, the air management, or how the movement toward or from breathing disturbs the stability of the body beneath.

6 – Look for Propulsion Problems

Use a drill to scan for ineffective entry and extension, rotation, catch shape or pathway, or the movement of the legs in relation to the torso’s rotation.

Always start by testing for frame and problems. For instance, if you turn off the legs and let them stream behind the body do your hips start to sink immediately? If you slow down your stroke to exaggerated slow tempo do you find you can’t hold a patient front arm? Or do you fall flat or have to turn onto your side to hold that pause?

If you don’t find a frame problem, then move on to streamline or stability. For instance, if you put a pause in your stroke right before you set the catch, do you lose velocity immediately (as if you are gliding in mud)? Does your extending arm cross toward your center line? Do your legs scissor while kicking? Do they spread sideways instead of vertical? Does the foot create a “thump” sound on each kick? Does it catch air and spread bubbles underwater?

Hone Your Subjective Senses

The use of the objective tools (a watch, counting strokes, tempo) is fairly easy to teach, because it involves things that are easy to observe and measure from the outside. The use of subjective tools, however, is both a science and an art and develops from lots of practice with regular testing (comparing to objective measurements) and exposure to others who use subjective tools skillfully in order to learn their tricks. Yet, these subjective measuring skills important for those on the mastery path to develop because by them you pilot your vessel and improve its flight.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Skill Learning

Did you know that your your brain extends throughout your entire body?

Yes. The nerve endings (all various kinds) reaching nearly every cell and covering every square centimeter of your skin are extensions of the brain itself. All those nerve endings on the skin’s surface are in constant contact with water flowing over the skin, detecting temperature, pressure, friction, etc. That is critical feedback for you while swimming.

We technically regard it as ‘subjective’ feedback because it is processed by our brain and not some inerrant ‘scientific’ instrument – but sensitivity to and accuracy in how that information is interpreted can be refined to a point where – for all practical purposes for a swimmer – it is objective.

Then we have proprioception. Technically, it means your ability to sense where your body parts are positioned and what they are doing without having to look at them. Interoception is your ability to sense the information coming from deep within the body and flowing through it (which bypasses your external sensory organs). It is the highly developed use of proprioception and interoception that the most graceful athletes and artists put to use in ways that leave us in awe. Yet these are not secondary, elective skills that only elite athetes can or should develop. You would need serious medical intervention to stay alive if you did not have some level of ability in these two areas. However, they do need to be developed to a higher level if any athlete would like to rise above the level of struggle and mediocrity.

For instance, if you have to lift your head and look forward to see where you are going or what track your hands are taking during the extension, then this is a sign of weakness in your proprioception. Using the eyes for assurance in what is happening is a replacement for proprioception.

Drills are used to build proprioception. When you have refined your proprioception you will be able to feel that your hand enters the water and extends forward just right without having to look at it. You will be able to feel that your spine is aligned and you are swimming straight as an arrow without having to look for some external assurance. You will be able to feel your legs streaming behind placing a compact kick within the envelope.

There are stages to developing this proprioception in drills, and it works best with the help of a partner or coach.

Imagine yourself in a drill position and going through this process of development:

- Someone directs my body part into correct position so I can feel the difference between ‘wrong’ position and ‘right’ position.

- Someone shows me (by demonstration) the difference between ‘wrong’ position and ‘right’ position to I can form a mental map of it.

- Someone mirrors for me (or shows me video) of what I am doing wrong, and where to make the change so that I can do it right so I can recalibrate my brain’s perception.

- Someone gives me verbal feedback (play-by-play) as I am doing the movement so I can make corrections in the middle of the movement.

- I recognize the feel of water, the ease in my body, and the absence or presence of certain natural forces when I am doing the movement well.

- I recognize the changes in the feel of water and the natural forces if I deviate from correct even a little bit.

Drills are meant to connect your body with the water and with the natural forces through the development of your nervous system and attention. They are not there to act upon you like a machine, and you will get nothing from them by going ‘through the motions’ of a drill without understanding, attention and intention. Everything in the drills is meant to turn on and strengthen your subjective skills of proprioception and interoception. So you will begin with external help and feedback from a coach, a friend, from a video camera, or from your own eyes, but all that external help and feedback should be urging you towards using your own internal senses to find and hold excellent swimming position and movement patterns.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Skill Learning

What are Drills?

In the most common understanding, drills are activities we use to isolate a part of your body position or movement pattern and make it easier to focus on that part to train it or correct it.

A drill can be fast or slow, active or passive, moving or stationary, whole stroke or just a part of it.

A drill requires attention and understanding of exactly what you are trying to learn or correct. The whole point is that a drill enables the mind to focus and improve control. Only when you are focusing attention on the skill purpose of the drill is effective drilling is occurring. If not, it does not matter how many repetitions you do.

The main purposes of a drill…

- To slow things down in order to expose improvement opportunities (weak spots)

- To isolate a certain area of the stroke so that specific corrections can be made one at a time

- To give the brain the ideal conditions it needs to make motor corrections and imprint them deeply

- To refocus the swimmer’s attention

- To heighten the swimmer’s sensitivity to external and internal feedback

- To rest one area of the body/brain so that another can be challenged without distraction or competition for resources

There is also a ‘drill mode’ mindset – this is where you maybe be doing what appears to be normal speed, whole stroke swimming to someone looking from the outside, but inside you are still focusing intently on improving some feature of your technique – we call this ‘whole stroke swimming with cues’. You could even be in the mode while doing a racing event! It’s a matter of paying attention and having an intention to protect or correct some feature of your performance.

Types of Drills

There are different types of drills we may use:

- Visualization

- Rehearsals (on land, or standing up)

- Stationary drills

- Limited movement drills (isolating just a part of the movement)

- Slower-motion whole stroke

- Whole stroke with modifications

Drill work is often assumed to require moving slowly, though that doesn’t always need to be the case. And Slower does not necessarily mean Easy. One way you can adjust the challenge level of the drill is to change the speed of your movements. If you are having a hard time successfully controlling the movement then slow it down. If it is getting too easy then speed it up.

One of the mantras in martial arts is, “Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.” Another we use is, “Slow it down to speed it up”. The idea behind this is that we need to establish precise neural control over the movement skill – to hook up the wire in the brain through slow, careful movement – and once that wire is hooked up we make it stronger by gradually turning up the challenge level of the work we are doing around that skill. As it get stronger the command signal will become more precise and travel faster – the movement skill will become easier to execute, faster and more powerful.

There are different purposes to doing drills at different movement speeds and intensity (amount of force or power applied). We can do them in these different ways:

- Slow speed, low intensity when first getting a grasp of a new skill

- Slow speed, higher intensity when building more strength around the skill

- Moderate or higher speeds, low intensity when building higher precision and fine timing

- Moderate or higher speeds, higher intensity when building resilience to performance stress

Each combination has a particular purpose and are very effective when applied to different parts of your skill development.

Moving from Drills to Whole Stroke

You use drills in order to no longer need them any more. You are practicing in order to master swimming, not to master drilling. The idea is to start with simple drills to get a grasp of the new skill. As your skills get stronger the drills gradually increase in the level of challenge taking you into whole stroke swimming and then to whole stroke swimming in challenging conditions.

Some people can get stuck in drills as an end in themselves, avoiding whole stroke altogether, but this is not what they are intended for. The point is not to become good at doing drills, but to become good at whole stroke swimming, and then to take that whole stroke where ever you want to go. Drills are a tool, not a rule. Use drills when they help, and don’t use them when they don’t help. When the drill is not help that is a sign you need to redesign the drill until it does. You must know the skill you are working on and how the drill is meant to strengthen it, and it has to hold your attention with the right amount of challenge – too easy and you will tune out, and if too hard you will get frustrated.

Here is a progression of mixing drills and whole stroke…

- Set that involve only drills, no whole stroke

- Alternating between drills and whole stroke

- Whole stroke with drills used for active rest between repeats

- Whole stroke with drills used for a tune up just before each set

- Whole stroke swimming with cues (in the ‘drill mode’ mindset)

In early stages of your development you may spend a lot of time doing drills. In later stages of your development you may spend nearly all your time doing whole stroke with cues. Even when advanced, when you take up a new skill or make a significant change to one of your patterns, then you may temporarily revert to spending time doing more drills around that new skill to help it get wired into your body and then more quickly return to whole stroke swimming most of the time.

When to Change Drills or Adjust them

Two important concepts to think about:

- Failure Rate

- Autonomous Control

Failure Rate

It is good to start with a drill that allows you to most easily execute the skill – you need to see and feel that you can successfully do it under easiest conditions.

But to get stronger you need to challenge your control over it right up to the failure point. You will do best and the work will be most interesting to you when the drill is challenging enough that you have to really give your best attention to it to avoid failure.

If the drill has you failing more than half of the time, and you are not making useful observations (learning from) the failures, then the drill is too hard. In this case, you may need to reduce the challenge level slightly.

If he drill is so easy that you can easily execute the skill without failure nearly all the time, then it might be a good reminder, but you risk losing attention. In this case, you may need to increase the challenge level slightly.

The sweet spot for drill challenge is where you are working right up to your failure point, and experiencing failure maybe 10% to 30% of the time and it requires your full attention to keep it there. It is also important that you are understanding what is causing the failure, that you are learning from it.

Autonomous Control

What you are ultimately aiming for is to autonomous control over the skill, or in other words, you are able to execute the skill, under challenging conditions, without having to pay attention to it. It is wired into your brain and body and even under stress your body moves the way you trained it to move.

At some point drill are just not going to be challenging enough. You will want to subject your skill to whole stroke swimming. And then easy whole stroke swimming will not be challenging enough, and you will want to subject it to more difficult conditions, like focusing on other things, going higher speeds, longer distances, in rougher water, or in other race-like conditions. You will have practiced executing this skill under challenging conditions so often that it your brain becomes able to control that skill without your conscious attention on it.

There is no way around the gradual increasing challenge of the work that must be done. To provoke this development in the most enjoyable way you get to learn the art of setting your drill complexity right in your optimal level of challenge, and keep it there – not too much and not too little. From the effect of hundreds of successful repetitions sprinkled with enough failure, of work done in a variety of forms, your abilities will increase (which means your failure point will move back) and you will keep incrementally increasing the drill complexity (i.e. the challenge level) to stay near the edge of your abilities and keep provoking them to grow.

If you find the work boring, then there is a problem in the drills design, or in the attention or in the intention of your work.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 27, 2020 | Open Water, Practice Design

If you feel some tension between your need to maintain swimming fitness and your need to carefully integrate new skills that can’t quite hold up under regular training stress yet, you may wonder how to get the best of both, without losing too much from either.

Early on in a season of acquiring new skills or in reformatting some big feature of your stroke, you may need to slow things down to get that new movement pattern etched into your nervous system. This may mean doing more drill and short stroke segments and short repeats for a while, until those skills feel more familiar, more easily performed and sustained under easy swimming conditions. Eventually, you may feel ready to start swimming longer, uninterrupted distances and your attention and control over technique will feel ready for it.

However, you may already have a good foundation of skill built up and are just making some minor adjustments that are not so hard for you to stay focused upon under normal fitness training. Or, you may be starting a process of making big changes, yet you still feel the pressure to maintain more intense training while you try to integrate those new skills into it.

Granted, it will be better (easier and shorter) in the long run if you can ‘slow down’ for some period of time to more carefully integrate your new skills under easier conditions that allow you to hold attention and form successfully. But you can still do whole stroke swimming with some or most of your new skills, if you choose just one or two cues at a time and you hold yourself to a high standard with those.

Use your drill and short-slow-and-careful stroke work in the first part of your practice and during active rest between fitness sets. Use this time to set a few, very specific cue that you want to insert into your fitness work and maintain. This kind of intention and concentration will actually make your fitness work even more challenging!

Using the activities you’ve learned in your live lessons or in the videos, just take some time to tune up your sensitivity and control over a few particular parts of the stroke a drill, then move into whole stroke swimming holding just one or two cues at a time. Within whatever normal swim set you are doing, choose a distance or duration in which you will hold your attention on that chosen cue – this too will be like lifting weights, and you will notice attention fatigue.

So, choose 2 or 3 cues and rotate though them at regular intervals, while continuing to swim whole stroke. This is called ‘swimming with cues’. If at any time while swimming along you lose the feel, lose sensitivity, lose control, then you can stop for a moment to move into drill mode to regain that control, and then resume the set.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Skill Learning

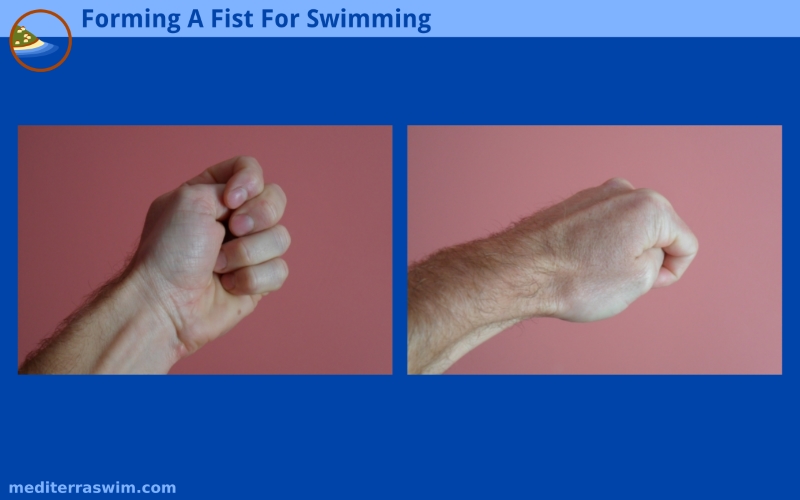

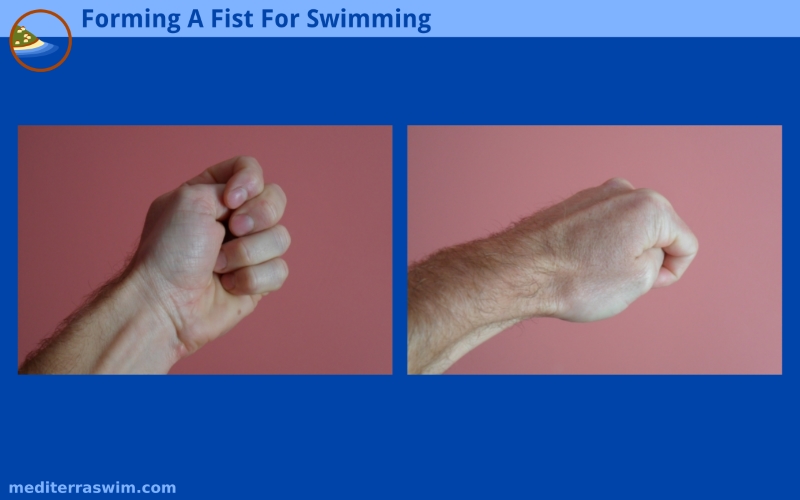

Fist swimming is the opposite of swimming with hand paddles. Rather than expanding the surface area of the hand with paddles, fist swimming reduces the surface area of the hand.

Why would a swimmer want to do this?

To force your body to figure out how to get a better grip on the water using the entire forearm, not just the hand. This kind of constrained activity is called a ‘self-limiting’ exercise in therapy lingo. The idea is to reduce capability in one way in order to (lovingly) force the body to figure out another way (a better way) to do the task.

By reducing the surface area you are urged to use more of the arm to get a sufficient grip – this is strengthening your motor connections and your muscles in precisely the way you want them to be used while swimming.

In a 25 (m or y) pool fist swimming might increase your SPL by +2. But it is a great exercise to attempt to lower your SPL with fist swimming.

It is important that you form the fist with as little tension in the hand as possible. Tension will reduce the sensitivity in your hand and arm, making it harder to feel the water. You may experiment with placing a small object in your hand to hold, or keeping your thumb inside or outside the grip of your fingers.

To allow complete relaxation in the hand you can purchase actual ‘fist-gloves’.

Fist gloves are nice in this regard, but the can break and wear out quickly. So, you might be motivated to either make your own fist or to invent your own fist-gloves out of something less expensive.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Drill Demos

The one-arm drill is useful for a variety of skill projects and focal points, including recovery, entry extension, stability, 2-beat kick, and breathing timing.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Drill Demos

Below is a demonstration of various rehearsals one can do to practice best entry arm position in freestyle…

A series of rehearsals to help you find a better entry arm position.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 23, 2020 | Drill Demos

Below are various drills we use for developing the 2-Beat Press, what we formerly called the 2-Beat Kick.

A standing rehearsal for practicing a single foot motion with hip torque.

A standing rehearsal for practicing foot-hip torque connection.

A drill for practicing bi-lateral foot and hip connection, in Superman position.

A drill for practicing the connection of foot and arm extension, one side at a time, in Spear Switch.

A drill for practicing the set up for 2 Beat Kick on one side, in Skate position.

A series of drills for practicing the connection of foot to core rotation.