by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Practice Design

Making decisions on how to response to your results in the middle of a practice set is one of the most important skills for a self-coaching athlete. Knowing how to keep your practice activity in the sweet spot of challenge and effectiveness for its intended purpose is what will allow you to be most productive with your precious practice time. We would call this a feature of Following an Organic Training.

As you get into a practice set, you have three options:

1 – If the challenge level is just right, keep going with the assignment.

2 – If the challenge level is a little too low (too easy), then increase the complexity or challenge level in some slight way.

3 – If the challenge level is too high (too difficult), then either decrease the complexity or challenge level in some slight way. Or, it may be a sign that one of your performance systems has had enough for the day.

When is it just right, too much or too little?

The answer is quite subjective to your personal situation. But here is a guideline:

Just Right

You are feeling challenged, and are experiencing failure maybe 20% to 40% of the time. This is the sweet spot of challenge, to provoke your brain and body to improve.

Too Little

You are not feeling very challenged and are experiencing failure maybe 10% of the time or less.

Too Much

You are feeling overwhelmed by the challenge and are experiencing failure more than 50% of the time. This could come at the beginning or end of the practice set – it was too difficult from the start, or later in the swim the challenge exceeded your resources. You may consider your need for rest and stop that set.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Skill Learning

In your ongoing practice of swimming you eventually come to know what your best slippery form feels like and what your best efficient stroke feels like – these sensations are subjective – and you come to know what your objective metrics should show – such as a certain pace or heart rate or stroke count.

You swimming practice is meant to work through these three tasks, in this order of priority according to physics:

- Remove or reduce the natural forces working against you

- Recruit the available natural forces that can assist you in moving forward

- Apply your own power – just the amount needed, and in the precise location and timing

Probably 90% or more of the struggles faced by common swimmers are solved by working on just the first two points above. However, it is easily observed that most swim programs seem to devote 90% of the time working on only #3, and they get far less improvement than they could because they haven’t sufficiently solved the first two points.

A Drill is a Diagnostic Tool

Drills are activities that allow you to isolate a part of the body or a part of the movement and make it easier to pay attention and control that part. Drills can also be used to help you diagnose a problem. By using a drill you can isolate a part of the body you suspect is having a problem and there you can experiment to find out what is causing that problem so you can correct it, and also notice what is working as it should so you can protect those features.

The fact that you can feel that something is wrong is a very good sign, and it is the first step to improvement. The next step is to find out exactly what it is so that you can work on it.

But there is the problem of having hundreds of details to search through in the stroke! And if you don’t have a coach there to notice immediately and bypass all that you need a way of organizing your search for the root problem. So, this is where you take up a diagnostic map and guide you in a way to use drills to test various parts of the stroke in an orderly way and help expose the weak spots.

Your Diagnostic Map

The three points above examine the problem from a physics viewpoint. Then we overlay that physics viewpoint with physiological/neurological view point to build this Diagnostic Map:

1 – Look for Frame Problems

First use a drill to scan for problems in the frame, in the connection of the upper and lower parts of the body, in the balance, and in the stability (side to side balance).

2 – Look for Streamline Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems in rotation, in connection of the streamline side of the body, in the arm or scapula position, in the position of the head or legs.

3 – Look for Stability Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems in balance when moving the recovery arm, in the lead arm, in the legs, in the rotation angle.

4 – Look for Connection Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems in the connection of the entry arm to the torso, or with the catch and the torso rotation.

5 – Look for Breathing Problems

Use a drill to scan for problems with the position of the head, the timing of the turn, the air management, or how the movement toward or from breathing disturbs the stability of the body beneath.

6 – Look for Propulsion Problems

Use a drill to scan for ineffective entry and extension, rotation, catch shape or pathway, or the movement of the legs in relation to the torso’s rotation.

Always start by testing for frame and problems. For instance, if you turn off the legs and let them stream behind the body do your hips start to sink immediately? If you slow down your stroke to exaggerated slow tempo do you find you can’t hold a patient front arm? Or do you fall flat or have to turn onto your side to hold that pause?

If you don’t find a frame problem, then move on to streamline or stability. For instance, if you put a pause in your stroke right before you set the catch, do you lose velocity immediately (as if you are gliding in mud)? Does your extending arm cross toward your center line? Do your legs scissor while kicking? Do they spread sideways instead of vertical? Does the foot create a “thump” sound on each kick? Does it catch air and spread bubbles underwater?

Hone Your Subjective Senses

The use of the objective tools (a watch, counting strokes, tempo) is fairly easy to teach, because it involves things that are easy to observe and measure from the outside. The use of subjective tools, however, is both a science and an art and develops from lots of practice with regular testing (comparing to objective measurements) and exposure to others who use subjective tools skillfully in order to learn their tricks. Yet, these subjective measuring skills important for those on the mastery path to develop because by them you pilot your vessel and improve its flight.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 28, 2020 | Skill Learning

Did you know that your your brain extends throughout your entire body?

Yes. The nerve endings (all various kinds) reaching nearly every cell and covering every square centimeter of your skin are extensions of the brain itself. All those nerve endings on the skin’s surface are in constant contact with water flowing over the skin, detecting temperature, pressure, friction, etc. That is critical feedback for you while swimming.

We technically regard it as ‘subjective’ feedback because it is processed by our brain and not some inerrant ‘scientific’ instrument – but sensitivity to and accuracy in how that information is interpreted can be refined to a point where – for all practical purposes for a swimmer – it is objective.

Then we have proprioception. Technically, it means your ability to sense where your body parts are positioned and what they are doing without having to look at them. Interoception is your ability to sense the information coming from deep within the body and flowing through it (which bypasses your external sensory organs). It is the highly developed use of proprioception and interoception that the most graceful athletes and artists put to use in ways that leave us in awe. Yet these are not secondary, elective skills that only elite athetes can or should develop. You would need serious medical intervention to stay alive if you did not have some level of ability in these two areas. However, they do need to be developed to a higher level if any athlete would like to rise above the level of struggle and mediocrity.

For instance, if you have to lift your head and look forward to see where you are going or what track your hands are taking during the extension, then this is a sign of weakness in your proprioception. Using the eyes for assurance in what is happening is a replacement for proprioception.

Drills are used to build proprioception. When you have refined your proprioception you will be able to feel that your hand enters the water and extends forward just right without having to look at it. You will be able to feel that your spine is aligned and you are swimming straight as an arrow without having to look for some external assurance. You will be able to feel your legs streaming behind placing a compact kick within the envelope.

There are stages to developing this proprioception in drills, and it works best with the help of a partner or coach.

Imagine yourself in a drill position and going through this process of development:

- Someone directs my body part into correct position so I can feel the difference between ‘wrong’ position and ‘right’ position.

- Someone shows me (by demonstration) the difference between ‘wrong’ position and ‘right’ position to I can form a mental map of it.

- Someone mirrors for me (or shows me video) of what I am doing wrong, and where to make the change so that I can do it right so I can recalibrate my brain’s perception.

- Someone gives me verbal feedback (play-by-play) as I am doing the movement so I can make corrections in the middle of the movement.

- I recognize the feel of water, the ease in my body, and the absence or presence of certain natural forces when I am doing the movement well.

- I recognize the changes in the feel of water and the natural forces if I deviate from correct even a little bit.

Drills are meant to connect your body with the water and with the natural forces through the development of your nervous system and attention. They are not there to act upon you like a machine, and you will get nothing from them by going ‘through the motions’ of a drill without understanding, attention and intention. Everything in the drills is meant to turn on and strengthen your subjective skills of proprioception and interoception. So you will begin with external help and feedback from a coach, a friend, from a video camera, or from your own eyes, but all that external help and feedback should be urging you towards using your own internal senses to find and hold excellent swimming position and movement patterns.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 27, 2020 | Practice Design

In order to make progress you need to measure and monitor information coming from your body and from your performance. Your progress will depend on improvements inside the body which correspond to improvements in performance (swimming easier, swimming farther, swimming faster) measured outside the body.

Measuring Quantities, Measuring Qualities

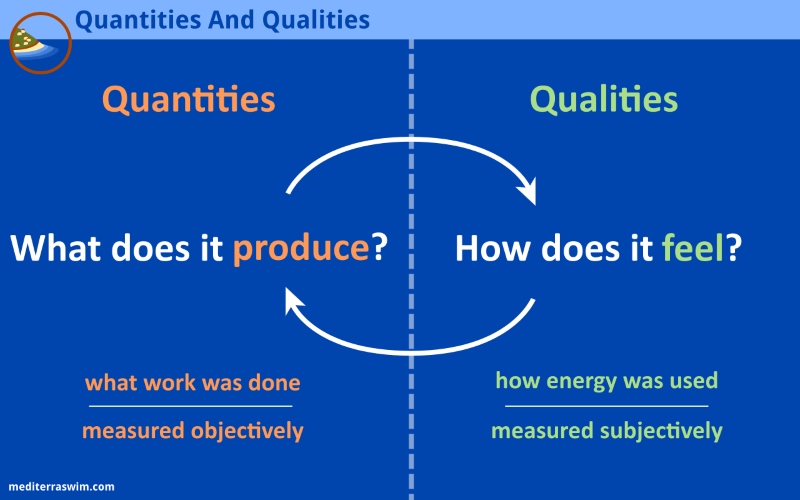

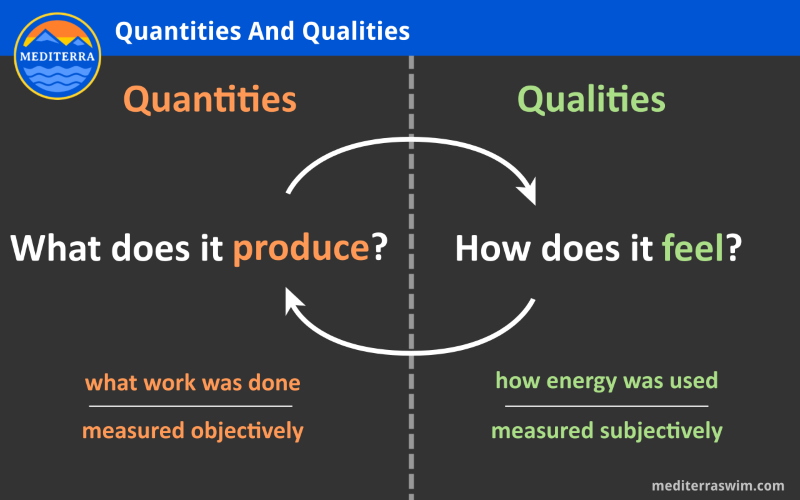

What is happening on the inside of the body (how does it feel?) – a quality – will correspond to what is happening outside the body (what does it produce?) – a quantity.

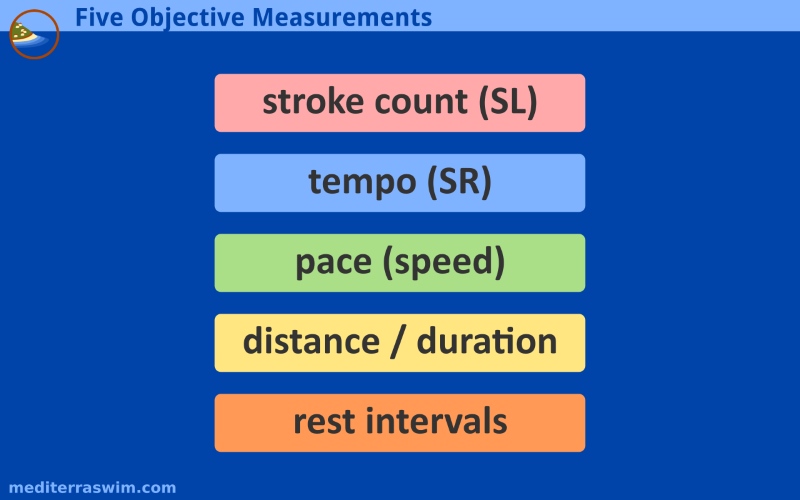

You can read more about these internal (subjective) measurements in this post on Two Essential Measurements. And these are the external (objective) measurements.

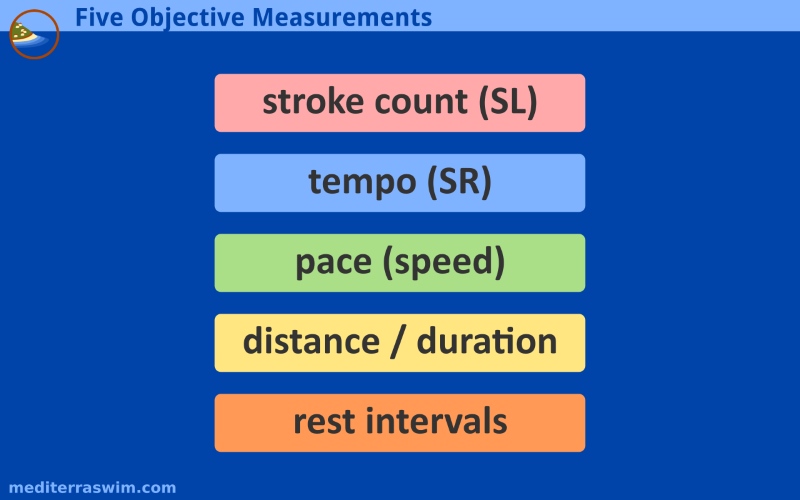

In every practice, in every swim, you will monitor those internal sensations, or what are called ‘subjective feedback’. Some of these may be assigned specifically:

On many of your practice sets you will also measure external results, or what are called ‘objective feedback’. Some of these may be assigned specifically:

- Stroke count

- Tempo

- Pace

- Distance or duration

- Amount of rest

For a simple rating system, see Simple Rating System for Your Practice Results.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Practice Design

The first objective I have in swim practice is to bring my body and my mind into the water. The next objective is to bring my mind into my body. The third objective is to bring all my internal systems online and into a unified, cooperative state for higher performance. Then I am ready to work for the day.

If I cannot achieve this unified state within the normal time frame it usually indicates that I am fighting an illness and need to get out to rest for the day. Or it may be that I should remain in this Tune-Up process longer.

Silent Swimming is a very useful activity in Tune- Up (a.k.a. Warm Up) for accomplishing these objectives.

I recommend at least 8 minutes for this. 12 minutes is about minimum for myself.

Basically, the task is to produce as little noise, splash, bubbles (= lowest turbulence) as possible. It is not about moving slow, but rather it is about moving gently and that usually compels us to start slow and wait for the systems to unify and tell us when its time to turn things up. This is based on the premise that our bodies really do want to work hard and perform at highest capacity. The body has inbuilt wisdom for how to get there each day and a signal language through which it communicates that wisdom. We need to learn how to read those signals and respond cooperatively.

Silent Swimming is an exercise, or more so a discipline, in listening and responding to those signals.

In Silent Swimming you may start out gently and increase tempo as you feel your body relaxing, the joints loosening up, the tissues starting to slide and yield to a full range of motion. Blood will migrant to the areas of your body that need to work. Heart rate and respiration will increase and come into a working rhythm. Your attention to your nervous system and especially to the surface of your skin will awaken and focus. Energy production will turn up and urge you to use it.

by Admin Mediterra | Sep 24, 2020 | Practice Design

There is a particular way that our skill-mastery-oriented practices are designed and how progress is measured. We would like you to pay attention to this pattern and become familiar with it. Then you will be able to use the same pattern to design your own practices.

Objectives

In each section you are given a specific skill objective to work on. For those skills you are given a description of what success for this skill should look like and feel like. There may be additional instructions for the skills or focal points for What To Aim For and What To Avoid.

These assignments have both a quantity and a quality component. Each practice will assign the quantities of distance or duration (like “repeat drill 3 times”, or “Swim 3 rounds of 4x 100 whole stroke”) or have you choose them. Anything you can measure externally, like time and distance and stroke count is what we call a quantity.

And, in each section there are descriptions of the qualities you will aim to achieve – like, “keep your hips and shoulder brushing the surface for 3 seconds”, or “keep your fingers soft”. There are several qualities described in each assignment, so you have a lot to explore.

Becoming a smooth, economical swimmer – getting more work done for less expense in energy and stress – is totally dependent on the development of these qualities, for they all correspond to how you use energy in the body. You can swim faster or farther with more energy expense and stress in the body, or learn to do it with less. Our mastery-minded approach to training specializes in the latter. To this end, your success in the drills and whole stroke is measured by your qualities more than by your quantities accomplished.

The drills and whole strokes are meant to help you achieve these qualities. Developing these qualities are the point of the practices – the better the qualities are the more quantity you will be able to handle – swimming farther, faster and swim more often with eagerness. In practice you may need to decrease the challenge on your brain (complexity) to make it possible for you to succeed, or you may increase the number of repeats in order to give yourself more time to figure it out. Either way, you are aiming to achieve that quality.